Difference between revisions of "Digital technologies/3D printing/3D modeling- Intermediate"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==[[Digital technologies/3D printing/3D modeling- Intermediate/TinkerCAD (contd.)|TinkerCAD (contd.)]]== | ==[[Digital technologies/3D printing/3D modeling- Intermediate/TinkerCAD (contd.)|TinkerCAD (contd.)]]== | ||

| − | == Design for 3D Printing == | + | == [[Digital technologies/3D printing/3D modeling- Intermediate/Design for 3D Printing|Design for 3D Printing]] == |

If your design is to be used in (electro-)mechanical assemblies in which there are interfacing components, it is important that you understand three basic tolerancing concepts and to keep them in the back of your mind when modeling or more generally designing these assemblies. | If your design is to be used in (electro-)mechanical assemblies in which there are interfacing components, it is important that you understand three basic tolerancing concepts and to keep them in the back of your mind when modeling or more generally designing these assemblies. | ||

Revision as of 21:51, 20 July 2022

TinkerCAD is nice for smaller parts with very little complexity. However, since it is not NURBS based nor parametric, it lacks major functionality. It is strongly suggested at this stage that TinkerCAD, Blender, Cinema 4D or other polygonal modelling (non-NURBS) applications be set aside for parametric CAD software, such as Autodesk Fusion 360 (free for students. teachers, and educators), Dassault Systèmes Solidworks (available through Remote Apps) or PTC OnShape (completely online, free for students and educators) be used for mechanical design, as models made with such software contain much richer data that allows going from CAD models to manufacturing data. Polygonal modelling remains, however, an important tool for Scan to CAD, and such the intermediate CAD user should have a complete understanding of polygonal modelling software such as TinkerCAD.

TinkerCAD (contd.)

Design for 3D Printing

If your design is to be used in (electro-)mechanical assemblies in which there are interfacing components, it is important that you understand three basic tolerancing concepts and to keep them in the back of your mind when modeling or more generally designing these assemblies.

- Form: The form of a part refers to the overall dimensions and the shape of the exterior surfaces of a component. Think of a flaw referring to form as a print that ended up not matching the base geometry that was used to create it in CAD due to adverse physical variables during the printing process. Examples follow:

- A sphere may end up slightly oval once printed due to improper cooling, etc.;

- A pillar might end up tilted to one side due to improper belt tension between the belt axes, etc.;

- A pin feature might end up too large to fit its mating hole due to the printer outputting too much material when producing the outer walls of the feature (the inverse can also be true).

- Position: Position refers to the distance separating a feature and an (ideally) meaningful reference (i.e.: the distance between a hole and the side of a part, or between two holes). Thankfully, flaws pertaining to position are rare on a properly tuned printer, as the printer does not have any information about existing references other than the build plate. If tuned properly, the printer will always print a feature at a position (X,Y,Z) distance relative to another feature, because that is what the gCode will tell it to do. You can imagine, however, that if the part is warped, the 'build plate reference' is no longer valid, and such, warped parts almost always have features out of position unless the meaningful reference (interfacing feature) used in the design is not the build plate. However, since the build plate reference is such an important one to define the Z position of features (for the printer, that is), making your meaningful reference something other than the build plate does not always guarantee you good positional tolerance independent of warping.

- Surface: The surface finish of a part is a rather complex subject. In 3D printing, and for typical applications of 3D printed parts, it mostly refers to the mean (statistical) difference between the height of cusps and valleys on a part and their deviation from that mean, at a macroscopic level. The most important consideration is that when 3D printing, most surface finishes are quite rough (deviate significantly from the mean), and thus are sanded down considerably to knock out the cusps left by the printer. This post processing can negatively affect the form of the final part.

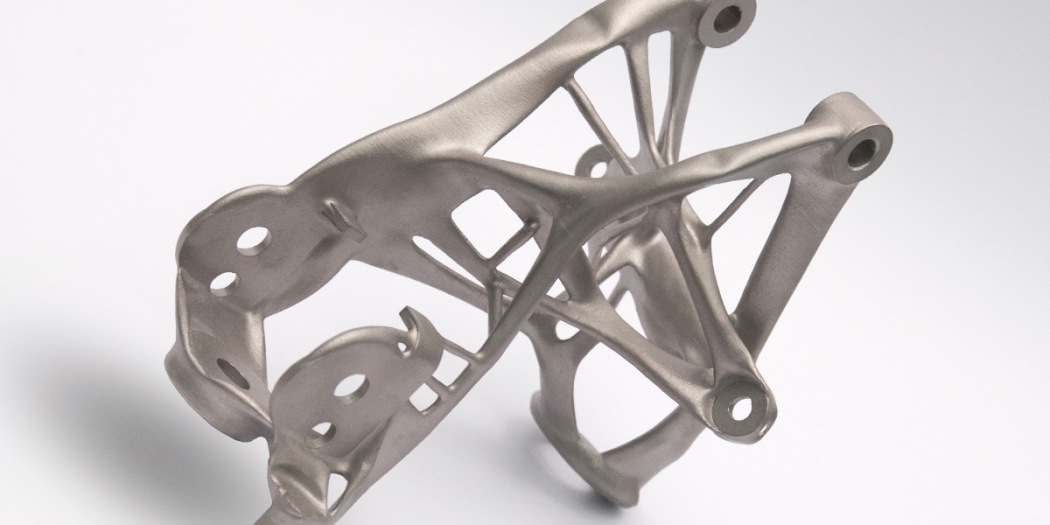

Note that a proper mechanical fit between components demands a good tolerance on form, feature position, and surface finish, such that it is typically impossible to obtain a proper fit when 3D printing, and that if you are considering the 3D printing of critically interfacing components, 3D printing should not be used unless post processing is built into the design. For mechanical designs, you will notice that a main application is brackets. This is because brackets only need good positional tolerance on holes and mating faces, which 3D printing can almost always provide (the tolerance on form for holes is not that important since they are typically clearance holes). However, since some brackets are easily laser cut, 3D printing brackets is only done under certain specific conditions. It certainly has shown its commercial use in cost cutting by replacing intricate multi-part assemblies by generatively designed (we'll say computer generated for now) parts, as shown in the picture below.

CAD Extensions

The following are extensions for common polygonal and NURBS formats.

Polygonal Formats

NURBS Formats

Standard

- ISO10303 - Standard for the Exchange of Product model data (*.STP, *.STEP)

- AutoCAD Drawing Exchange Format (*.DXF/*.DWG)

- Initial Graphics Exchange Specification (*.IGES) (standard last updated 1996)

Software-Specific

- DS Solidworks Parts (*.SLDPRT)

- DS Solidworks Assemblies (*.SLDASM)

- DS CATIA V5 Parts (*.CGR/*.CATPart)

- DS CATIA V5 Assemblies (*.CGR/*.CATProduct)

- PTC Creo Parts (*.PRT)

- PTC Creo Assemblies (*.ASM)

- Fusion 360 (*.F3D)

It should be noted that Fusion360 stores files on the cloud, such that locally saved .f3d files are not commonly encountered. It should also be noted that OnShape does not have a file format given it is hosted entirely on the cloud.

Using Parametric NURBS Software

References

- ↑ CarrusHome (2021). GM Explores 3D printing, generative design for next gen parts. Consulted on 05-05-2022 at https://www.carrushome.com/en/gm-explores-3d-printing-generative-design-for-next-gen-parts/